It would be an obvious thing to proclaim that no place and no one’s safe from the brutality of terrorism in Pakistan. There are no safe havens here where the faith-charged barbarians can’t and won’t strike. However, and ironically, over the last couple of years, what was once one of the most edgy and troubled provinces of Pakistan, Sindh, has remained nervously quiet (if not entirely peaceful).

As suicide bombers and car bombs go off with an audacious frequency right across the NWFP, Punjab, Balochistan and Islamabad, Sindh and its capital, which is also the country’s largest city, Karachi, has largely remained ‘peaceful’ – at least for the last two years.

Of course, this peace has very little confidence in itself and always seems to be on the brink of losing its fragile hold to the wrecking ways of the Taliban, the Al Qaeda, and related clusters of holy madness; but so far the province of Sindh has managed to ward off the bloody spat of reactive violence perpetrated by the Taliban and their sympathisers in the wake of the government and the army’s operation in Swat, and now Waziristan.

One can locate the source of this (albeit fragile) peace in the unwavering strength various strains of non-puritanical Islam (such as Sufism) and the politics and sociology of the shrine culture have demonstrated in much of Sindh.

Conventional politico-religious parties such as the Jamat-i-Islami (JI), Jamiat-Ulema-Islam (JUI), and Jamiat-Ulema-Pakistan (JUP) have never been able to exercise any worthwhile political, social, or electoral power in the interior of Sindh, and neither have the more militant and fanatical off-shoots of these parties such as the Sipah Sahaba Pakistan and the Sunni Thereek (formed in 1990 and considered to be the result of factionalisation in the JUP).

The interior of Sindh has for long been the bastion of political influence and electoral power of the secular Pakistan Peoples Party (PPP). Other forces that also exercise some political influence in this area are various Sindhi nationalist groups, and the Mutahidda Qaumi Movement (MQM), that enjoy pockets of support in the area. The only conservative political parties that can boast of some political and electoral influence here are squarely moderate in their religious outlook. These include Pir Pagara’s Pakistan Muslim League (Functional), Ghulam Mustapha Jatoi’s National Peoples Party, and Mian Nawaz Sharif’s Pakistan Muslim League (Nawaz).

The process of ‘Islamisation’ or more so, religious radicalisation undertaken by the Ziual Haq dictatorship in the 1980s through state propaganda and madrassahs to create puritanical jihadi groups for the so-called anti-Soviet Afghan Jihad, had little impact on the minds and hearts of Sindhis.

The shrine culture and its political and social tentacles were just too strong here to break; in fact, this culture was effectively used by Zia’s opponents (especially the PPP and Sindhi nationalists) during the three major anti-Zia movements that took place in Sindh (in 1981, 1983 and 1986).

Karachi, the capital of Sindh, offered a different story. Though the city has always been known as the only truly cosmopolitan city of the country with strong liberal and pluralistic overtones, till 1984 it was the only major city where fundamentalist politico-religious groups such as the JI and the JUP enjoyed their finest electoral hours.

Interestingly though, JI and JUP’s influence in Karachi was solely political – a case of reactive politics on the part of Karachi’s mohajir majority which, unlike the Sindhis, Baloch, Pashtuns, and Punjabis, was not directly linked to the land they lived on and thus had to define its ‘Pakistaniat’ by supporting the country’s non-ethnic ‘Islamic roots’ of creation.

The Political Islam displayed in the rhetoric and manifestos of the JI and the JUP appealed to the mohajirs landless refugee status, whereas as a social, cultural and economic entity, the mohajirs remained largely liberal in outlook. That’s why, though the JI and the JUP continued to enjoy widespread political support in Karachi, this did not affect Karachi’s other status of being Pakistan’s most modern, diverse and liberal centre of activity.

Through the 1950s, 1960s, and 1970s, Karachi was also the entertainment capital of the country, holding the most number of nightclubs, bars, cinemas, amusement parks, social clubs, and beaches with hundreds of ‘huts’ made to accommodate the thousands of Pakistanis and western tourists who visited these beaches. The city was also the country’s economic hub and bastion of higher education, boasting the largest number of factories, colleges, and universities.

On the other hand, Karachi also had the biggest slums. The largest continues to be located in the Lyari area, mostly populated by working-class ‘Afro-Pakistanis,’ a people whose ancestors were brought from Africa as slaves and soldiers first by the invading Muslims (from the eighth century onwards), and then by the Portuguese in the seventeenth century.

Other major slums of the city are made up of various ‘underclass’ and working-class mohajirs – most of whose families arrived from India after 1947 but, unlike many of their post-Independence refugee contemporaries, could not better their economic conditions – as well as Pathans, most of whom started arriving during the Ayub Khan dictatorship in the 1960s and have since been involved in the city’s economic activity as laborers, factory workers, and transporters. Biharis, who are Muslims from the Indian Bihar, most of whom moved to former East Pakistan after 1947, but started arriving in Karachi after East Pakistan became Bangladesh in 1971 also inhabited the city’s slums.

The widespread slums also meant that Karachi had the most pronounced crime rate in the country, but it is interesting to note that politico-religious parties had been more popular in the city’s middle- and lower-middle-class areas that voted for them mostly for political reasons (as discussed above); whereas the voting that took place in the city’s working-class and slum areas had more economic and left-leaning motives. For example, left-of-centre parties like the PPP have continued to win in Lyari and Malir’s working-class areas ever since the 1970 general elections, and the leftist National Awami Party (NAP) was strong in the Pashtun-dominated working-class areas, just as the defunct party’s off-shoot, the Awami National Party (ANP) – formed in 1986 – still is.

Karachi’s enthusiastic response to the JI-led Pakistan National Alliance’s protest movement – based on the slogan of Islam and shariah – against the ZA Bhutto regime in 1977 was more political in nature than ideological. Bhutto was a Sindhi (‘son of the soil’) and an autocrat, two things the mohajir majority of Karachi could not connect with keeping in mind its refugees-from-India status and its mistrust of the provincial system that replaced the old ‘one-unit’ system (after 1970) that did not recognise the provinces on ethnic basis.

But ethnicity become an even more prominent issue after Bhutto was toppled and hanged by Ziaul Haq – an event that the Sindhis will would never forgive the Punjabi dictator for.

Affected by the growing ethnic cleavages in the society, some mohajir student activists decided to form their own political group, as if demonstrating that the mohajirs too were a separate ethnic entity. Formed in 1978 at the Karachi University, the All Pakistan Mohajir Students Federation (APMSO) soon gave birth to the Mohajir Qaumi Movement (MQM) in 1984. The emergence of this distinct ethnic party happened at a time when Karachi had started to teem with a number of administrative, economic, and social problems, mainly due to overpopulation and the arrival of thousands of Afghan refugees who had started to pour into Pakistan at the start of the anti-Soviet Jihad in Afghanistan in 1980.

Many of these Pashtun Afghans started to populate the Pashtun-dominated slums and working-class areas of the city, plus the vast open areas just outside the city that were turned into permanent refugee camps.

Just like their Pakistani Pashtun brethren in Karachi, many Afghans too became laborers, petty traders, and transporters. However, many of the Afghans also brought with them huge amounts of weapons (pinched from American weapons consignments for the anti-Soviet jihadists), and drugs like heroin that had started to pour in from the outskirts of the anarchic Afghan-Pakistan border areas.

Unchecked entry of the Afghans leading to rapid population growth; the introduction of sophisticated weapons to settle scores and commit crime (the ‘Kalashnikov Culture’); drug mafias – many of whom switched from selling the less harmful and less profitable hashish to selling the highly addictive and lucrative heroin – and the utter lack of road sense and concern by transportation companies run by the richer Afghans in the city, all these gravely upset and altered the social and political landscape of Karachi, putting a tremendous burden on the once thriving economics of the city.

These coupled with the Zia dictatorship’s relentless ‘Islamisation’ moves that also saw radical religionists (mostly militant Saudi-funded Sunni groups) setting up a number of madrassahs and mosques in the city and whose sole aim was to indoctrinate and recruit young Pakistanis for the ‘Afghan jihad,’ turned Karachi into the most violent and crime-riddled city of Pakistan, which now also became a hotbed of sectarian strife.

The emergence and gradual popularity of the MQM meant the fading away of the political support conventional politico-religious parties like the JI and JUP enjoyed in the city. This also meant the beginning of another process, in which the relative social liberalism of the mohajirs began to also invade and colour the community’s otherwise conservative politics.

This process however would be rather slow to evolve, as the ‘rootless’ MQM and the huge mohajir support that it had bagged got into a series of tense conflicts with the province’s Sindhi majority, the Afghan refugees, Karachi’s Pashtun minority, and then with parties like the PPP, the JI, the PMLN, and eventually with the state itself.

Throughout the 1980s Karachi struggled with intense ethnic and sectarian strife, an unprecedented crime rate, a serious heroin problem, and a collapsing economy – a trend that failed to reverse itself across the ‘decade of democracy’ in the 1990s. The city had become a cultural and economic graveyard, and paled in comparison to what it had been before 1980.

In contrast to this, the last 10 years or so have seen Karachi unexpectedly regenerate itself – first at a tentative, unsure and cautious pace (during which it faced a number of suicide bombings, but during which the MQM also began to peel off its overwhelmingly ethnic and militant character). The pace of the social, economic, and cultural regeneration picked up after 2004, and the city started to demonstrate a new confidence and maturity.

Though still one of the most complex, diverse, edgy and populated cosmopolitan entities, Karachi’s relatively peaceful decorum in the face of the havoc being perpetrated by the extremists elsewhere in the country is due to some admiring compromises that the people and politicians of this city have struck in the last few years. Some of the factors fueling Karachi’s regeneration are:

• The acceptance by the state of Pakistan of MQM’s mainstream status as a political organ with a strong electoral influence that cannot be deterred through any form of Machiavellian maneuvers.

• A delicate but promising compromise struck between the secular political expressions of Karachi’s mohajir, Punjabi, Pushtun, Baloch, and Sindhi populations, namely the MQM, the ANP, and the PPP.

• The diverse population’s reflective understanding of the importance of social and political plurality and tolerance as a means to experiencing a strife-free and economically benefiting survival in the metropolis.

• The withering away of the political support that politico-religious parties such as the JI and the JUP once enjoyed and whose recent politics (especially the JI’s), encourages a myopic and isolationist world view that can be detrimental to the people of a cosmopolitan, diverse and economically vibrant city like Karachi.

• The relative lack of support (compared to the NWFP and the Punjab), that the city provided to various militant groups. Thanks to Karachi’s staggeringly ethnic and sectarian diversity, it was always tough for puritanical sectarian and Islamist groups to find much sympathy from the bulk of the city’s population.

• The overriding consensus against the Taliban, reached long before such a consensus was struck by Pakistan as a whole.

• A popular and prominent city government, supported across the board and among distinct ethnicities.

• The Sindh and city governments’ firm stands on the issue of Taliban cells in the city.

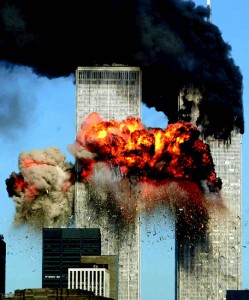

Eight years ago, two planes flew into two towers and the world changed. The United States initiated a ‘war against terror,’ which even today shapes foreign policy and ordinary lives from Washington to Baghdad, Kabul to Khartoum. With the war came game-changing rules: on one side suicide bombings and decapitations became a symbol of religious pride and anti-imperialism; on the other, wire tapping became an expression of patriotism, illegal detentions replaced justice, and torture was justified in the name of national security.

Eight years ago, two planes flew into two towers and the world changed. The United States initiated a ‘war against terror,’ which even today shapes foreign policy and ordinary lives from Washington to Baghdad, Kabul to Khartoum. With the war came game-changing rules: on one side suicide bombings and decapitations became a symbol of religious pride and anti-imperialism; on the other, wire tapping became an expression of patriotism, illegal detentions replaced justice, and torture was justified in the name of national security.

Hakimullah Mehsud has told BBC Urdu that Baitullah Mehsud died two days ago.

Hakimullah Mehsud has told BBC Urdu that Baitullah Mehsud died two days ago.