.

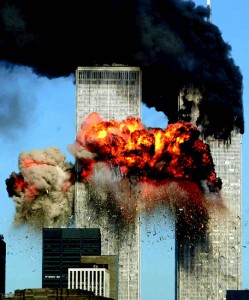

Eight years ago, two planes flew into two towers and the world changed. The United States initiated a ‘war against terror,’ which even today shapes foreign policy and ordinary lives from Washington to Baghdad, Kabul to Khartoum. With the war came game-changing rules: on one side suicide bombings and decapitations became a symbol of religious pride and anti-imperialism; on the other, wire tapping became an expression of patriotism, illegal detentions replaced justice, and torture was justified in the name of national security.

Eight years ago, two planes flew into two towers and the world changed. The United States initiated a ‘war against terror,’ which even today shapes foreign policy and ordinary lives from Washington to Baghdad, Kabul to Khartoum. With the war came game-changing rules: on one side suicide bombings and decapitations became a symbol of religious pride and anti-imperialism; on the other, wire tapping became an expression of patriotism, illegal detentions replaced justice, and torture was justified in the name of national security.

Across the globe, the events of September 11, 2001, sparked a new way of thinking about everything – self-determination, national sovereignty, justifications for war, the viability of democracy, the sanctity of borders. But even while new definitions were nebulous – posing challenges to long-held notions of statehood, freedom, and human rights – the US found it easy to craft its response to the attack on New York City.

Indeed, 9/11 was a defining moment that threw moral ambiguity out the window and blurred the lines between a strong response and a necessary response. After 9/11, neat lines between good and evil were drawn (even if ‘good’ included images of the atrocities from Abu Ghraib and ‘evil’ included attempts to bring efficient courts to places where the corrupt judicial system had failed communities).

In terms of American foreign policy, 9/11 also helped clarify goals for the post-Cold War agenda. Once the problem was identified (i.e. Islamic terrorism) the solution became obvious – democracy. In the earlier part of this decade, neocons within the Bush administration developed a narrative that suggested Islamic terrorism was the by-product of authoritarian regimes and the lack of pluralism in the Muslim world. In response to that narrative, the US continues (even under President Barack Obama) to export freedom and democracy every chance it gets. Iraq may have turned bloody, Palestine may have voted in Hamas, and Iran’s recent spurt of democratic activity may only have served to strengthen the status quo, but the headlines today, on the eighth anniversary of 9/11, are about the US’s determined efforts to defend the political process and recent elections in Afghanistan.

The ease with which America wiped out shades of grey so that it could focus on the stark, yet simple, contrasts between black and white has been replicated by the United Kingdom, the European Union, and even India.

But here, in Pakistan, we’ve had a harder time dismissing the logical consequences of historical trajectory and wading through murky moral waters. It has only been within the last few months that Pakistani support for the Taliban and Al Qaeda has plunged: according to a Pew Global Attitudes Project poll, until early 2008, 25 per cent of us had a favourable opinion of Al Qaeda, while 34 per cent had an unfavourable opinion (in 2009, nine per cent have a favourable opinion with 61 per cent unfavourable). Similarly, in 2008, 27 per cent of Pakistanis favoured the Taliban while 33 per cent were not in favour of them. Today, those figures are 10 per cent and 70 per cent, respectively.

This change in mindset towards the perpetrators of terrorism – both on Pakistani soil and abroad – has been hard won (and let’s be honest, it’s probably tentative and temporary). It has come after eight years of attacking and backtracking, negotiating and eliminating, extremism and moderation, resistance to the American mandate and, ultimately, cooperation.

Why has Pakistan had a harder time articulating its stance against terrorism than the US and other nations in the coalition against terror? Could it be because Pakistan has not endured a game-changing event such as New York’s 9/11, London’s 7/7 or Mumbai’s 26/11?

Or did it?

The fact is, terrorist attacks that have jolted the nation out of its complacency and ambiguity towards radical extremism have come fast and furious. As early as 2003, when General Pervez Musharraf was attacked, we have known that terrorists are capable of gripping the public in a clutch of fear and uncertainty. In the past two years, the audacity of their transgressions has only escalated: from the assassination of Benazir Bhutto to the bombing of Islamabad’s Marriott Hotel, innumerable suicide bombings at mosques during Friday prayers, attacks against Sufi shrines, targeted attacks on high-level government officials and the Sri Lankan cricket team, kidnappings, ambushes at security checkpoints, and, now, the shooting of school children from the Shia community.

But not one of these events – including the shocking death of former prime minister Bhutto – have galvanised the Pakistani public the way that 9/11 mobilised Americans (and their allies) against terrorism.

If we have learnt anything from 9/11 – or more precisely, our lack of a 9/11 equivalent despite the fact that terrorism is rampant – it is that there has been a failure in Pakistani nation-building over the past 62 years. When the Twin Towers were hit, it was New York’s tragedy, but all of America saw it as a turning point. Once Americans were under attack, it didn’t matter if they were Democrats or Republicans, liberals or conservatives, East Coast or West Coast. But here, the Marriott’s bombing was Islamabad’s trauma, the attack on the Sri Lankan cricket team was Lahore’s shame, and the assassination of Bhutto was Garhi Khuda Bux’s loss.

In Pakistan, the endemic problem of national fragmentation has prevented us from claiming each and every terrorist attack that has occurred on Pakistani soil as an atrocity against our own person and territory. Bombings in Jamrud are a problem for locals – they have nothing to do with you or me. The imposition of the Nizam-e-Adl in Swat was a predicament for the valley, not for Lahore or Karachi. The bombings of mosques, schools, hotels, and more was acceptable to any Pakistani whose daily life was not affected by the same. Has anyone every stopped to think that if we had reacted to the first terrorist atrocity after 9/11 the way the Americans had, there may not have been a years-long reign of terror to contend with?

So are we Pakistanis better or worse off without a 9/11 of our own? An event that has so much symbolic power that it launches a powerful nation out of the realm of international diplomacy and into the realm of rhetoric – where good fights evil, crusaders battle terrorists, and freedom triumphs over darkness – is dangerous. It is 9/11-like events that lead to things like the quagmire in Iraq and growing Islamophobia in Europe.

But to continue to see dastardly attacks as isolated incidents that can be justified on the basis of religion, geopolitics, and retaliatory logic is a failure to understand the magnitude of the threat that radical extremism poses to our social fabric. Is it possible, under any circumstance, for Pakistan to build and sustain a national consensus against terrorism, but without enduring the pitfalls of the United States’ post-9/11 experience?

src=’dawn.com’

November 23rd, 2009 at 11:43 PM

Pakistan